In Defense of the Big Syllabus, Part 1: The Comprehensive Syllabus

My husband, Stan, once worked at a company that had a particularly detailed employee handbook, with all kinds of stipulations about behavior in the office environment. One item that stood out was from the section about the office dress code. Among other things, employees were prohibited from displaying “visible underwear or the visible absence of underwear.” Stan and I were especially amused by the latter injunction. As Stan pointed out, why would the employee handbook contain this rule unless someone had, at some point in time, come to the office with a “visible absence of underwear” that somehow seemed inappropriate or unprofessional? This is the kind of picayune prohibition that would only be written down after-the-fact, because a workplace experience demonstrated a need for it.

Are your course syllabi driven by a “visible absence of underwear”? Is your syllabus a purposeful document, or is it an accretion of “rules” in response to administrative needs and student behavior? When I was an undergraduate, my professors often handed out syllabi that were just one or two pages, but today my own syllabus typically runs about ten to thirteen pages. Is all that necessary?

When I started writing this essay, I thought it was going to be an exploration of how to prune down the unruly rules-monster of a contemporary syllabus. But after further reflection, I would actually like to argue that the new normal in syllabi is a good development. Let’s call it the “comprehensive syllabus.”

The Surprising Research into Syllabus Length

Research in teaching and learning shows that a comprehensive syllabus fosters a better attitude in students. Several studies have asked students to read syllabi with different levels of detail and then answer survey questions about their expectations for the course and their assumptions about the instructor. Perhaps surprisingly, students in these studies actually preferred longer syllabi. Moreover, with a more detailed syllabus, students consistently were more likely to assume that the professor will be approachable, caring, well-prepared, promotive of critical thinking, engaged in their professional field, and more (see Harrington and Gabert-Quillen; Jenkins, Bugeja, and Barber; Saville, et al.).

Interestingly, it’s not just any kind of detail that helps make a better first impression, but specifically “course boundary” information delineating policies and expectations (Jenkins, Bugeja, and Barber, 133). I have sometimes been anxious that my 12-page syllabi will seem overwhelming to students, but in fact, the wealth of detail may be comforting. Students may feel as though they’re about to embark on a journey in a well-constructed vessel, not a leaky dinghy.

Yes, you may object, but do students actually read the syllabus? If you chat with any college-level instructor, the anecdotal evidence suggests “no,” and certainly I’ve gotten my share of emails asking questions about things that are clearly stated in the syllabus. That said, there’s surprisingly little research about how students actually engage with this key document. In one survey, 88% of students claimed that they use a syllabus as a reference tool and 80% say they use it to help with time management (McDonald et al.). Given that students overall claim that they prefer a comprehensive syllabus, I’m inclined to think that they do actually use it, if not by reading it word-for-word right at the start, at least as an important reference through the semester.

Examples in Practice

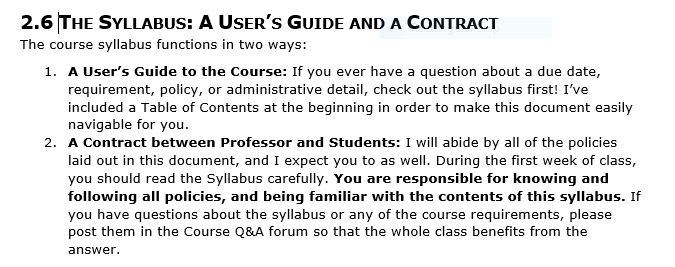

My own comprehensive syllabus assumes that students will use it as a reference tool, and I include this blurb describing the “user’s guide to the course”:

An example of how I frame my syllabus as a "user's guide and contract"

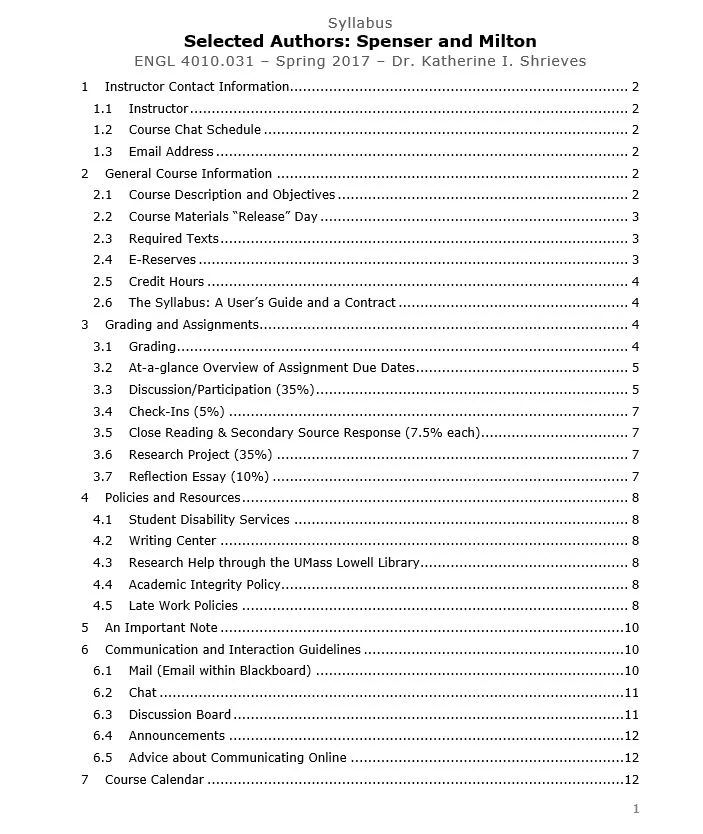

All that policy information isn’t helpful unless readers can find what they need, when they need it. To that end, each of my syllabi starts with a Table of Contents. In the electronic version of the syllabus, the items in the Table of Contents are clickable links that take readers directly to that part of the document (and I also include other clickable, internal references throughout to help readers navigate). Here’s an example of my syllabus Table of Contents:

Example of a table of contents from one of my syllabi

Much of my teaching takes place online, and in an online classroom, having a comprehensive syllabus is even more important, since the instructor can’t fill in gaps through informal classroom conversation as easily. The “syllabus as user’s guide” analogy becomes even more pertinent.

There’s a potential pitfall with the comprehensive syllabus, though, which is that it could alienate students if it comes across as obtuse and legalistic. In Part 2 of this essay, I’ll talk about why and how to create a syllabus that’s not only comprehensive but also engaging.

Works Cited

Harrington, Christine M., and Crystal A. Gabert-Quillen. "Syllabus length and use of images: An empirical investigation of student perceptions." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 1.3 (2015): 235.

Jenkins, Jade S., Ashley D. Bugeja, and Larissa K. Barber. "More content or more policy? A closer look at syllabus detail, instructor gender, and perceptions of instructor effectiveness." College Teaching 62.4 (2014): 129-135.

McDonald, Jeanette, et al. "19. Two Sides of the Same Coin: Student-Faculty Perspectives of the Course Syllabus." Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching 3 (2010): 112-118.

Saville, Bryan K., et al. "Syllabus Detail And Students' Perceptions Of Teacher Effectiveness." Teaching Of Psychology 37.3 (2010): 186-189. ERIC. Web. 9 Jan. 2017.